- Macular degeneration

- Excerpt

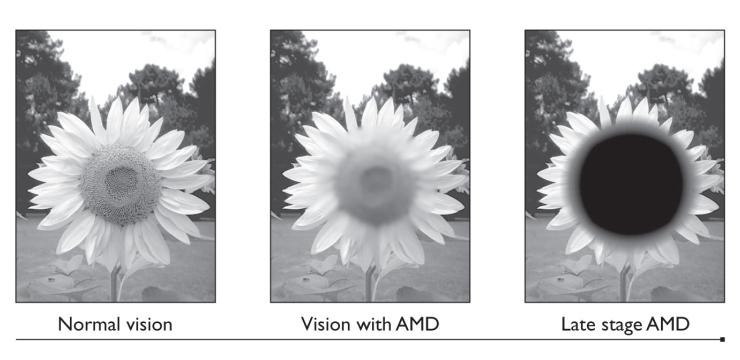

Loss of macular function (macular degeneration) impairs the eye’s capacity to focus, and what remains is an unsharp picture caught by the part of the retina that surrounds the macula. The textbooks speak of a loss of central vision. Most people who lose the center of what they see still retain the periphery, but the periphery doesn’t function as sharply as the macula. Because we look at things by way of central vision, macular degeneration forms a great obstacle to creating a good entire picture of what we are supposed to see. Macular degeneration is a rapidly spreading condition that affects millions of people. The onset of the condition appears mostly in people 50 to 60 years of age. Some authors call macular degeneration the leading cause of irreversible blindness among people older than 65 years. This is why the problem is referred to as age-related macular degeneration (AMD). AMD is extremely hindering because it affects all our daily activities.

The retina is the three-layered light-sensitive screen that absorbs and transmits the incoming pictures to the optic nerve. The outer layer of the retina, which catches the incoming pictures, consists of rods and cones. The rods are active in dim light, and the cones are active in bright light. In the center of the macula, at the spot called the central fovea, the retina consists only of slim and elongated cones. These cones have a special structure that aids the detection of details in the visual image. Because the light falls directly on these cones and on nothing else, the center of the macula is the area where the retina has its clearest vision. AMD is a form of retinopathy in the sense that the macula and its central fovea form an integral and essential part of the retina. These “clearest vision” parts of the retina are as dependent on the retina’s vascular system for nourishing and for carrying away waste products as are all the other parts.

The diabetic retinopathy studies mentioned above (click here) all fully apply to AMD. This is confirmed by the fact that earlier, during the 1960s, the Flavan clinical trials, mentioned at the beginning of this book, had already brought us proof of the very beneficial effects of OPCs on impaired vision. Depending on their symptoms, patients were administered 160 and 240 mg of OPCs isolated from the bark of the Pinus maritima. This treatment produced favorable results in patients who suffered from rapid bleeding in the eyes, from Eales’ disease, which is characterized by blocking of the retinal veins, from diabetic retinopathy, and from retinitis. I remind you of one of the Flavan patients, a 76-year-old woman, who suffered from a macular lesion and inflammations of other parts of her right eye. Taking a modest daily dosage of 80 mg of Flavan during a period of three months, she satisfactorily improved her vision, and as a bonus, she got rid of her morning headaches.